The year 1776 acted as a catalyst for these innovative ideas. Thirteen British colonies in America declared their independence from Britain and founded their own state, based on the ideas of the Enlightenment. The Patriots followed America’s example: after they had widely maligned William V – even the States-General compared him to the Duke of Alva – they forced him to flee in 1787. The Prussian king intervened, rehabilitated the stadtholder and forced the patriot leaders to flee to France.

The Prussian monarch had interfered because he believed the fall of the stadtholder could well be the beginning of the end for old Europe. Two years later it was obvious how right he had been. Taking their cue from the Americans and the Dutch, the people in France rose in revolt against the old rulers. (The red, white and blue French revolutionary flag was inspired by the tricolor of Netherland.)

The course of the French Revolution is only too well known: the absolute monarch Louis XVI agreed to convoke the Estates-General and in the years that followed the Third Estate, renamed the National Assembly (an assembly not of the Estates but of ‘the People’) and later reconstituted as the National Constituent Assembly, took over power. Subsequently, things got completely out of hand in a very bloody way until a ‘strong man’, Napoleon Bonaparte, restored order. A number of administrative innovations were introduced and because the French knew what was good for the world, they exported their revolutionary ideas to other countries. In 1795, they brought back to the Netherlands the Patriots who had fled to France. William V was driven out – this time for good. The Netherlanders welcomed the French and the Patriots as liberators.

While the French Revolution degenerated into Napoleon’s dictatorship, in the Netherlands began an unparalleled series of administrative experiments, creating great uncertainty for a full twenty years. It all started when the Patriots passed a number of reform laws. The separation of church and state, which had been respected for quite some time already, became a basic principle, and religious minorities such as Catholics and Jews were given full civil rights. After that, the hereditary transmission of municipal administrative functions was abolished. Furthermore, out-of-date institutions such as the guilds disappeared. The most important change was that the sovereignty of the provinces disappeared and the first steps were taken towards centralized government. From now on, sovereignty lay with the people as a whole

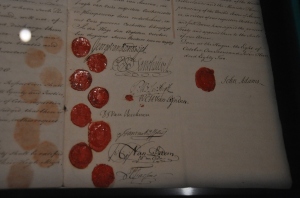

Netherland was no longer a republic of seven collaborating provinces. With a delay of more than two centuries, a united country had emerged, referred to as the Batavian Republic. In 1798, just as was already the case in the United States and France, the Netherlands got their own constitution, introducing general suffrage for men. It was still indirect, but it could have been the beginning of a real democracy like that in the United States. Executive power was assigned to a five-headed executive authority – a sort of cabinet – that supervised ministries. The wide endorsement of this first Dutch constitution was evidenced by the fact that when the English attempted to bring back the Prince of Orange to Netherland in 1799, they got no support from the Dutch population. When Napoleon wanted to take the democratic features out of the Batavian constitution in 1801, his draft constitution was rejected by a plebiscite. The French subverted the plebiscite by counting the non-voters as ‘yes’ votes, dealing a fatal blow to the incipient Dutch democracy.

In 1805, Napoleon again changed the constitution. A year earlier he had declared himself emperor and he now wanted to put in place a single unitary authority in the satellite states as well, believing that such an authority would be more ready to support his military campaigns. From the spring of 1805 to the summer of 1806, Rutger Jan Schimmelpenninck was leader of the Batavian Republic. He continued the policy of modernization and created an excellent government apparatus. He centralized taxation, did away with a large number of tolls, introduced land registration, improved education, brought in a uniform spelling system for the Dutch language, and transferred responsibility for healthcare from local authorities to special public health commissions. These commissions were the forerunners of the present Dutch Health Care Authority.

Schimmelpenninck’s furthest-reaching change was the introduction of the register of births, deaths, and marriages. For the first time, all people received family names, and some of those names still betray the political ideas of those years. If a Dutchman is called Prins, you can be sure that he has an ancestor who was hoping for the return of the Prince of Orange. Since in Belgium this register had been introduced before the spelling reforms, a discrepancy between the spellings of the same surnames still exists in Belgium and Holland today.

Because Napoleon was still not very happy about the Batavian contribution to the conduct of his wars, he placed his brother Louis Napoleon at the head of the new Kingdom of Holland, bringing to an end the traditional republican institutions. However, although the monarchy had been imposed from outside, it was not experienced as a bad thing. The first king of Netherland certainly did not lack good-will. He tried to learn the language, set up local government offices in the countryside, introduced the Civil and Criminal Codes, continued the modernization of the tax system, and took other measures to stimulate the economic recovery of the new kingdom. Setting up the Royal Library and the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences were two of these.

Despite everything, the French despot remained dissatisfied with the level of Dutch support in his wars. Furthermore, his brother Louis Napoleon had postponed implementing a number of measures and, when introduced, had failed to monitor them. That cost Louis his throne. Napoleon annexed the Kingdom of Holland and French customs offices were set up to insure that no business was transacted with the enemy. The Emperor had heard that during the Eighty Years’ War the Dutch had sold cannons to the enemy and was determined to prevent a repetition. The Dutch economy, which was already in difficulties, was now completely ruined and the enthusiasm which most people had felt for the reforms quickly evaporated. What nobody had thought possible now happened: the Netherlanders began to look back longingly to the time the Prince of Orange was in power.

In the years 1810-1813, the French presence in Netherland was that of a force of occupation, complete with censorship and raids to draft soldiers for Napoleon’s Russian campaign. The Dutch had already lost about ten thousand men on the Eastern front when Napoleon called for a new batch of conscripts. It was the straw that broke the camel’s back: the Dutch revolted. Actually, the revolt did not amount to much: sentry boxes were pitched into the canals and customs offices set on fire. Napoleon, however, was not in a position to retaliate as he needed all his troops to defend France after the Russian catastrophe. In November of that year, the last regiments of the occupation army quietly withdrew from Netherland.

>> to the next section >>